Just before COVID-19, I discovered that my website of over 20 years was hacked. It’s taken me some time to get it back up and running, but it’s missing a lot of content that I had added over the years.

Where I’ve been for the past five years

A student explained to me earlier why she uses Dropbox instead of Google. She told me “Google knows enough about me – they don’t need to also see my files.” She proudly pointed to her monitor, where a piece of paper covered the webcam lens: “They don’t need to know everything about me.”

This student had taken a digital studies course DIG 211: Surveillance Culture, and understood all the ways in which our use of the internet (and of ‘free’ apps, in particular) serves as a powerful source of data: for whom, we don’t really know, but the student was clear about her disdain for “The Corporations.”

I’ve been meaning to dig deeper into my own location history in Google Maps (whether your location history is on or off), ever since I discovered that my daily life consists of a triangle – home, office, cafeteria, sometimes a grocery store; during my youngest son’s high school soccer season, my triangle includes various high schools in Mecklenburg County.

Fortunately, Lifehacker wrote about an online tool that allows you to create a heat map of your Google Location History (her map looked more exciting than mine). My first data point in location history doesn’t appear until October 2013, so the map above is essentially for the last five years.

What does the map above tell me? I’ve spent time in two places – US and China.

Zooming into the various locations in the US, I see that almost all the places I’ve been to are colleges or universities, academic conferences, or family. My takeaway is that this is similar to the message of my daily triangle – I go to places for work or family.

Zooming into China, it gets a little better. I spend most of my time in Shanghai or other fieldsites in China, but at least it shows that I took a vacation (with my family) to Taiwan.

The interactive Location History Visualizer can be a big timesuck – it allows you to drill down to specific locations, so you can see more specifics about particular places – addresses where you’ve stayed overnight (since there are more of these datapoints, assuming you didn’t forget your phone somewhere), roads that you’ve traveled.

So now Google knows what I already knew – I don’t get out much. Capitalize on that.

Digital Persona Non Grata

I see myself as an early adopter (or maybe an innovator, according to Everett Rogers), ever since I bought my first DEC Rainbow 100 using CP/M-86 in 1984 and a modem that I would put the handset into to connect to the VAX computer in Mallinckrodt (the Chemistry building at Harvard). I think my first website was published in 1993, and I published an early article on listserv activism in 1999 or so. I’ve always believed in maintaining some kind of digital presence, and have tried to think critically about my own cyborg subjectivity since reading Donna Haraway’s classic manifesto and Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (and other cyberpunk).

However, after reflecting more about my digital persona for the DIGPINS workshop, I believe that I’m really not a digital native, but more of a digital immigrant (we get the job done). To think more about what I do digitally, workshop members were supposed to do a VR mapping exercise, a task that I resisted because I don’t like drawing by hand.

Instead of this reflective exercise, my first instinct was to find out what my digital presence was, at least according to the Big G. To do this, I opened an incognito browser in chrome and searched “Fuji Lozada.”

Many of the links I found were expected – my official Davidson page shows up first, followed by my personal page, and then of course the RateMyProfessors.com page. I found pages that I had forgotten that I’ve set up (e.g., medium.com, researchgate.com) as well as citations that I had not set up (e.g. religionlink.com). I even found old boxscores from college lacrosse games that I had refereed many years ago! Since Laurian Bowles is also part of this workshop, I repeated the search for her, for comparison:

What immediately jumped out was how my incognito search for her featured her Twitter posts, while my public Facebook page was listed for me. I am not as active on Twitter as Laurian, and she doesn’t use Facebook at all – and Google immediately recognized that! In fact, I’m not too social on social media in general.

So I kept going with the analysis of my digital persona, and used R to scrape the top 50 listings for an incognito search of “Fuji Lozada.” (While I could have just cut-and-paste the results, I’ve been playing with different types of webscraping.) You can see the results here. I didn’t have time to do more analysis, but the next thing I would do is perhaps increase the number of search results and do some coding to see what the Big G thinks my digital persona is.

So while I enjoyed reading about the benefits and challenges of our digital persona, as Pasquini writes, I’m less worried about the context collapse that Michael Wesch writes about (who at one time was the number one video on YouTube) than what in China is called the “human flesh search engine” (人肉搜索, sometimes compared to doxing), where internet/social media vigilantes can destroy lives and reputations, create chaos and confusion – sometimes just for the laughs. I was reminded of this issue through a NYT magazine article, ‘When the Revolution Came for Amy Cuddy‘ – it’s well worth the read. I’m not taking a stance on ‘power posing’ or p-hacking (that would take much more space), but the relevant point of this story for the DIGPINS workshop is that this took place because of digital technologies and social media. Without TED talks, an obscure social psychology journal article may not have taken disciplinary arguments into popular discourse; without listservs, email, and web sites like Data Colada and Slate, methodological critiques would not have resulted in such personal trauma. Need I say #Gamergate?

And the article in the late 1990s on flaming that I didn’t write (which has since been better done by Gabriella Coleman) further reinforces how I use my digital persona – although the V/R mapping doesn’t show it as well, much of what I do is largely for work. Given the space, I think the icons would be more widely spaced apart, with the personal digital tools like flickr and instagram being located more to the left, perhaps “renting” resident, while my institutional digital tools like vimeo, WeChat, and Facebook/Twitter leaning more towards “homeowner” resident. I also wasn’t quite sure if digital tools like Dropbox, Google Drive, Wunderlist, or WordPress (not WordPress.com) count as digital tools creating a digital persona, but I added those to the map anyway because they are tools that I more regularly use.

Work Smart, Not Hard: Use Zotero

Think of Zotero (a free, open source, easy to use program) not only as a citation management tool, but a program that lets you compile and organizes research sources. I use it to collect sources (especially when starting a new project), organize topics within a particular project, and share them with others. Using zotero from the very beginning of a project will help you work smart and efficiently – and it generates bibliographies automatically!

Why use Zotero?

Installing and Configuring a Zotero Library

- Create a free Zotero account

- Go to zotero.org and select Register (upper right hand corner)

- Fill in the registration information and verify the account via your email

- Install a library

- Go to zotero.org and click on Download Now

- Choose Zotero Standalone

- Also install a browser extension (below) to link your library with your preferred browser

- Also install a browser extension (below) to link your library with your preferred browser

- Configure your library

- In your Zotero library, click on the gear icon and select preferences ->sync:

- In your Zotero library, click on the gear icon and select preferences ->sync:

- Enter in your account information

- Click the Green sync button in the upper-right hand corner

- After you’ve synced Standalone and your browser, try the following:

- Go to a library database and locate an article

- Save to Zotero with your browser extension

- Go to Standalone and create a folder

- Drag your new item into this folder

- Check to see if Zotero grabbed the full text or a screenshot of your item

- Add a note or tag to your item

- Go to a library database and locate an article

For more questions visit the library’s Zotero Guide: http://davidson.libguides.com/zotero or e-mail askalibrarian@davidson.edu

Stalking your professors using Outlook

(Updated 29 Aug 2017 for Office 365).

One of the benefits to going to a liberal arts college is going straight to professors for help or advice. But outside of office hours, which should be posted on their website or in front of their office, how do you know when they are in? Other than teaching class, as faculty we spend a good chunk of our time going to various meetings, working in laboratories or libraries, and sometimes eating lunch.

One way to find out when faculty are available for individual meetings is to search through their schedule; many universities and colleges (like Davidson) now require their faculty to keep their Outlook calendar (or whatever office suite is used) up to date. The following instructions are specific to Davidson, but this functionality in Outlook is available to many others.

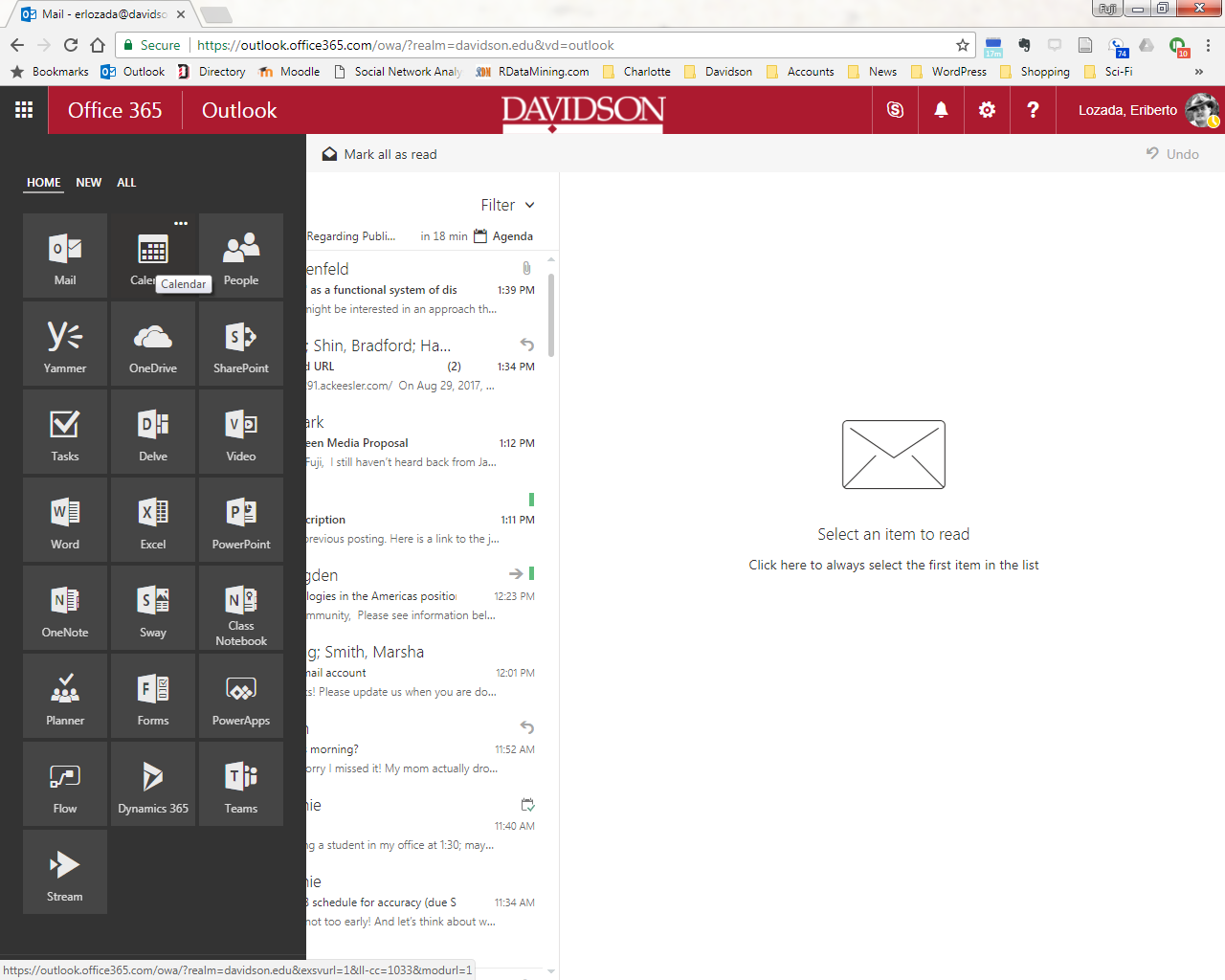

You do not need Outlook set up on your computer; as Davidson students, you can access Outlook through your web browser. Here are step-by-step instructions for using Outlook to stalk your professors. If you don’t feel like watching the video, you can read the instructions below the video.

- Go to your Outlook account, which at Davidson is “http://webmail.davidson.edu” (or “outlook.davidson.edu” or “office365.davidson.edu”) and sign in.

- Once you are logged on, you will either see the Office 365 web app or your outlook email (depending upon how you log in). But click the box icon on the upper left corner of the webpage and click on Calendar.

- Once you’ve clicked on Calendar, you will see your own calendar (which is probably empty, unless you use Outlook calendar to organize yourself). Then click new to set up a new meeting, and you will then see a new window pop up. Look for People and type in the name of the faculty member you want to meet (type in their surname). As a shortcut, you can type their userid (e.g., erlozada) and the faculty member should come up. Select the right person.

- On the right column that says Suggested times, you will see the date, duration, and a listing of times. If you’ve pre-selected a time, you can look in the People column to see if the faculty member is free. Otherwise, you can scroll down the Suggested Times column and see times that are open by looking for the meeting icon (see the picture below). You can change the date of the meeting by clicking on the date in the Suggested times column. Note: Times that are blank mean that time is not open; open times are those with the meeting icon.

- Once you found a time when your faculty member is free, you can either request the time by Outlook by selecting the start and end time at the top of the window and sending a meeting request or just note the time and date that is free and email the professor about meeting at that time. Double-check that you are on Eastern Standard Time. I’ve noticed some students have requested times when they think I am free based on Pacific Standard Time (which I believe is the default setting for Office). You can check this by clicking on settings (the gear), options, General, and then checking “Region and time zone.” Here’s a quick video to show you how to change your time zone settings:

This is the best way to pin down a time for an individual meeting with a professor. It’s much easier for your faculty member to schedule something like this, instead of sending two or three emails back and forth listing possible times to meet.

Office hours are also good times to meet, but that’s first-come, first-serve. With a scheduled appointment, you won’t have to wait.

Printing a Fabric Poster

My colleague Helen Cho has had enough with travelling with poster tubes to academic conferences. She’s decided to instead have her poster printed on fabric, something that can be easily transported in her carry-on bag. In helping her figure out the best way to do this, I found the following review from the American Society for Cell Biology. In anthropology, we don’t use or value posters as much as we should, so the best source of advice could be found among the scientists who do value posters for academic presentations.

If you’re not looking forward to the prospect of traveling with a giant cardboard tube, yet you’re reluctant to return to the days of the multiple-panel poster, consider printing on fabric.

https://www.ascb.org/careers/how-to-print-a-fabric-poster/

Jessica Polka recommends a service called Spoonflower. She suggests using a performance knit that brings out colors and has good wrinkle-resistance. In 2013 prices, she finds the cost of a 36″ x 58″ poster (including shipping) with a 10 calendar day return time is $25.00 (2014 Update: prices haven’t changed in a year, $24.60 with shipping).

This looks like a much better alternative to paper posters. With all the poster presentations that students have done over the years, my office is covered with rolls of paper. With polyester knit, I can maybe make shirts or other clothing with old posters!